Dear Reader,

Welcome to our weekly mailbag edition of The Bleeding Edge. All week, you submitted your questions about the biggest trends in technology. Today, I’ll do my best to answer them.

If you have a question you’d like answered next week, be sure you submit it right here.

Hello Jeff:

When you recommended QID as a hedge I thought it was brilliant. I subscribe to a couple normal stock picking services. Some of them are hinting the bottom is in. Seems impossible to me. Would you share your thoughts on that subject with us. best regards,

– Frank L.

Hi, Frank. Thanks for writing in. I’m glad you’ve found our hedge strategy useful.

To catch readers up, from recent research published in The Near Future Report, I recommended subscribers buy an “insurance policy” for today’s market.

We sold off several holdings, raised capital, and took a larger position in the ProShares UltraShort QQQ (QID) fund. QID is a double inverse fund. That means if the Nasdaq goes down 1%, our fund goes up 2%.

The strategy of using QID as a hedge helps to protect our overall portfolio in the event of a larger drop in prices. It also enables us to profit even when the market drops. It is designed as a short-term hedge, most likely to be held for less than six months. I believe the bottom will arrive within that timeframe.

Another way to view a security like this is as an “insurance policy.” We hope we’ll never need it, but we’ll be glad to have it.

And I agree with you, Frank. I don’t think we’ve reached the bottom of this tough market yet. So, it’s worth holding on to the hedge for the time being.

As readers likely know, much of the volatility this year is a result of both destructive economic policy and the monetary policy being pursued by the Fed and other central banks. The Fed has hiked rates much higher and much faster than almost anybody predicted (myself included). The below chart gives us some idea.

As we can see, the Fed is now hiking rates higher and faster than any other period in recent history. And it is very clear that Jerome Powell—the Fed Chair—will keep going for the foreseeable future.

Powell did leave the door open to smaller hikes in the months ahead. But my working assumption is we should expect fifty basis points (increase of 0.5%) hikes in December and January. As a result, we should position our portfolios for a tough few months leading into the first quarter of next year.

My concern is that this pace of rate hikes will cause something to “break” within the global financial system.

For instance, the current pace of rate hikes has strengthened the U.S. dollar to a two-decade high relative to other global currencies. In the past, a dollar this strong has resulted in debt crises.

In the early 1980’s, the strong dollar contributed to the Latin American debt crisis. That’s when many Latin American countries were unable to pay their dollar-denominated debt.

Another concern—which many would say is impossible—is that the U.S. could experience a sovereign debt crisis. U.S. government debt stands at $31 trillion. And with new spending like the Inflation Reduction Act—another $737 billion—federal debt is going higher.

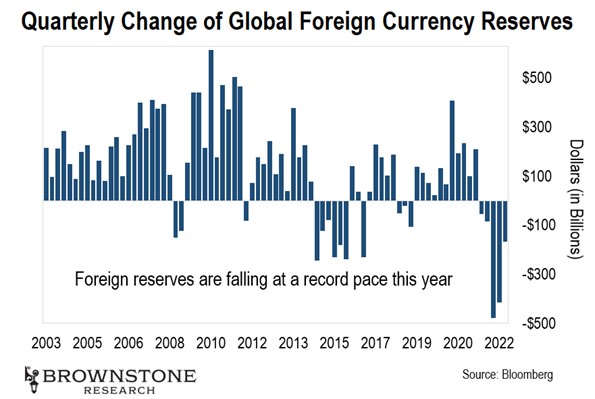

The U.S. government will be forced to finance this profligate spending with the sale of U.S. Treasurys. But as the next chart shows, foreign governments have been offloading Treasurys at an alarming rate this year.

If new government spending can’t be financed by tax revenue (deficits in fiscal year 2021 were $2.7 trillion) and foreign governments are unwilling to finance government expenditure through Treasury purchases, then cracks will start to form.

At that point, the Fed will have no choice but to step in and backstop the Treasury market. In that scenario, we’d see more liquidity in the form of quantitative easing. That’s precisely what happened with the U.K. back in September. And this has already happened this year in Japan as well.

I know some readers may be skeptical that could ever happen to the U.S. The dollar is the world’s reserve currency. Common thinking is that there will always be an active market for U.S. debt. And I certainly hope that’s the case.

But foreign countries are being forced to sell their U.S. dollar-denominated assets to pay for U.S. dollar-denominated goods because of the decades-high strength of the U.S. dollar (resulting from Fed policy). Until that changes, we’re in for trouble.

The impact of the rising interest rates is already devastating the mortgage and housing market. And car loan defaults are jumping higher as well. We can see the cracks already.

There is more to come, most likely in the first quarter. That’s when I expect we’ll see our bottom, no later than April.

And one final point…

To some, it might seem odd to be both long and short a market. The concept of a hedge, or insurance policy, is the easiest way to think about it. But another way to think about these two opposing positions is time horizon.

Positioning our portfolio for a potential drop in the market has a shorter time horizon. We expect to hold and sell our QID fund for a profit in less than six months.

But our long positions have a longer time horizon. These are positions that I know will recover quickly after the Fed pauses and then starts easing to “save” the markets and reduce volatility. We’ll hold those positions for more than a year for the purposes of long term capital gains (lowest tax rate).

Greetings, Mr. Brown

Would you be so kind as to let us know how to make sure that a start-up company is legit? Aside from contacting the company directly, which might not be the best way to handle the task.

– Ef T.

This is a great question. How do we assess a private company before we invest? Because these are private companies, there are no public earnings announcements. There are no regular earnings calls with the executives. As angel investors, we’re always working with incomplete information.

It’s good for you to ask this question. Because you’re right. An angel investor can speak with the founder, or founders, but how can we determine if they themselves are legit?

There are many things that investors can do to verify individuals and companies and the legitimacy of their projects. It requires some legwork and investigative skills. And it helps to have a network to draw upon.

Quick profiles from LinkedIn of founders can quickly reveal any possible connections in your network. It’s very rare for me to speak with someone who isn’t only one or two steps away from someone that I know well.

That’s the benefit of being an angel investor for more than two decades, and an executive for more than 35 years.

I also look to see if the companies have taken investments from other angel investors or venture capital funds. Strong investors are always a good sign of a high quality project, and often I speak with those that have already invested to learn more.

It is always useful to speak with others from that industry who may be aware of that company/founder as well. This is helpful to understand competitive positioning, how that product/service will fit into the industry, and of course confirm the legitimacy of the company/founder as well.

There have been times when I’ve reviewed legal documents concerning incorporation and checked addresses related to the company.

I remember one specific situation many years ago. I discovered that the corporate headquarters of what was positioned as a successful, emerging company was an apartment building with no office space.

Big warning sign. I passed.

There are of course times when I travel to a company’s headquarters to see it with my own eyes. I’ve done this with both private and public companies. Boots on the ground research is always useful.

I’ve also spent hundreds of thousands of dollars over the years on information resources that most normal investors normally wouldn’t have access to. This provides me and my team the ability to gain access to information that is always useful in our analysis.

Aside from determining legitimacy, there are several things I always research before I ever recommend a private investment. This is the same analysis I perform before I invest my own capital.

First, I always ask if the technology or product make sense for its market. Is there a clear vertical (i.e., a narrow market where the tech can flourish)? Is the company doing something entirely new and unique? Or is it just moderately better than what exists in the market today?

This seems an obvious first step, but we’d be surprised how many angels get tripped up right from the start.

I also consider if the company has a realistic vision to bring their product or service to market. In other words, the company might have a fantastic product or service, but if it can’t bring it to the market, then what’s the point?

Understanding the company’s “go-to-market” strategy is an important thing I always research.

When speaking with founders I want to get a “feel” for how they operate. Do they have a realistic plan for the business? Do they have a plan to responsibly deploy investor capital? Do they have a track record of successful businesses?

In the past, I’ve walked away from private investments just because I felt I couldn’t trust the executive team.

And finally, I always ask myself if the valuation makes sense given the company’s current progress. I have something of a chip on my shoulder with this last point.

One thing I hate to see is a private company raising capital from retail investors at unrealistically high valuations.

They assume retail investors won’t understand the nuances of valuation. And they think they’ll be able to get away with raising capital at an absurd valuation.

This benefits them because it allows the company to raise more capital for less of the company. It disadvantages investors because they get less for their money, and it basically sets investors back in their investment by years.

What typically happens is that if the company progresses to an institutional round, it happens at a lower valuation at the expense of the earlier investors – who took on more risk at an inappropriately high valuation.

This is a red flag for me whenever I see it. It really bothers me.

Private companies would never pull this stunt with venture capital. Any company pulling these shenanigans are not worth our time or our investment. That’s why I spend so much time analyzing valuation before I make a recommendation.

Hi Jeff,

Can you either direct me to a resource or tell me why I don’t understand the last column of your bond chart. Is it based on current prices? Please explain.

Thanks for recommending these bonds. I think they are a great addition to the stocks.

– Louise T.

Hi, Louise. I’d be happy to walk through our bond portfolio. I’m sure it would be helpful for several subscribers.

To catch readers up, earlier this year, we added a new strategy to Exponential Tech Investor. We began adding convertible bonds in high growth companies —I like to refer to them as “X-Bonds”. They provide us downside protection while maintaining our upside potential.

A convertible bond is very similar to regular corporate bonds. They have a coupon (we can think of this as a regular interest payment), and they have a predetermined maturity date where we will reclaim the par value of our bond (usually $1,000 per bond).

What makes them unique is the convertibility feature. As the name suggests, the bonds can be converted into equity of the underlying company at any time before the maturity date. And this is the feature that gives us the great upside potential. The chart below is a great example.

In 2016, Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) issued one of these bonds to the market with a 2.125% yield. That might not seem like much, but the return came with essentially no risk for a high-quality growth company like AMD.

The only real “risk” to these bonds is that the company goes bankrupt before maturity. But I don’t view that as a realistic possibility for our companies. That’s why I spend so much time looking at a company’s financial health before recommending any bonds. And in this instance, there was/is no way AMD was going to go bankrupt.

And investors who held this bond ended up doing much better than 2.125%. If investors purchased these bonds and held them through to 2022, they would have seen 1,000% returns.

This is only possible because of this convertibility feature. As the value of AMD’s stock climbed, the value of the bond went higher.

It’s an elegant strategy for today’s tough market. In essence, our worst-case scenario is we’ll simply hold the bonds through to maturity. We’ll collect a great yield to maturity as a result.

And if stock markets turn around, we’ll retain our upside potential and sell our bonds for a great profit.

But to answer your question, let’s walk through how to interpret our bond portfolio. Below, we’ll see one of our holdings. It’s a convertible bond offered by Alteryx.

Here’s what each data point tells us.

Company: This is the company offering the bond. In this case, it’s Alteryx.

CUSIP: This is a unique identifier that will help us identify the correct bond. We should give this figure to our broker when purchasing these investments.

Maturity Date: This is the date we will receive the par value of the bond (usually $1,000).

Coupon Rate: This is the regular payment we can expect to receive from the bond.

Conversion Price: This is the level at which we can convert our bond. In other words, we want to see Alteryx’s stock rise above this level for the bond to rise above the par value.

Conversion Ratio: This is the ratio that we can convert our bond at. In this case, one bond could be converted for roughly 5.28 shares in the company at the conversion price.

Yield to Maturity: This is the annual yield we can expect if we hold the bond through to maturity. The yield to maturity is a combination of the coupon rate and the difference between our purchase price and the par value.

Open Price: This is the price of the bond at the time of our recommendation. This is purely for tracking purposes. Individual entry prices for subscribers might be slightly different.

Buy-up-to Price: This is my recommended level for purchasing the bond. Purchasing the bond above this level does not make it a “bad” investment. It just means we’ll accept a slightly lower yield to maturity.

Return: This is the change in value we’ve seen for the bond since recommending it. Even if this figure is negative, readers shouldn’t be concerned. Remember, so long as we hold through to maturity, we’ll reclaim that par value ($1,000) of the bond and secure a great yield to maturity.

I hope that helps, Louise.

That’s all we have time for this week. If you have a question for a future mailbag, you can send it to me right here.

Have a great weekend.

Regards,

Jeff Brown

Editor, The Bleeding Edge

The Bleeding Edge is the only free newsletter that delivers daily insights and information from the high-tech world as well as topics and trends relevant to investments.

The Bleeding Edge is the only free newsletter that delivers daily insights and information from the high-tech world as well as topics and trends relevant to investments.